My most valuable garden journal entry is three words: “Courgettes died, frost.” I wrote it on 3 May 2021, after a late cold snap killed every seedling I had planted out the week before. I was gutted at the time. But that entry has saved me every year since. I do not plant courgettes until mid-May now, no matter how warm April feels.

That single failure taught me more than a dozen successful harvests. And yet for years I resisted writing down what went wrong. My journal was full of optimistic planting dates and proud harvest photos. The disasters went unrecorded, as if pretending they did not happen would make them hurt less.

It did not. I just kept making the same mistakes.

Why failures teach you more than successes

A garden journal full of successes feels good to read. “Tomatoes ripened beautifully.” “Beans cropped heavily.” “Best courgette year ever.” But what do those entries actually teach you? Not much. Success confirms what you already suspected: that you did something right. It does not tell you what to avoid.

Failures are different. Every failure reveals something specific about your garden — the climate, the soil, the timing that actually works here. A note that says “Sweetcorn did not mature, planted too late in June” tells you exactly what to change next year. A note that says “Sweetcorn was great” tells you nothing you can act on. (For more on what to track beyond failures, see what to track in your garden journal.)

The problem is that failures feel bad. Nobody wants to document their disasters. So we skip over them, hoping to forget. And then we forget the lesson along with the pain.

I have killed the same plant three times because I forgot I had already tried it. Melianthus major, a beautiful architectural plant that cannot survive my cold, wet winters. I bought it in 2019, watched it die, and somehow convinced myself to try again in 2021. Dead by February. In 2023, I saw one at a garden centre and thought “that would look lovely by the shed.” I was reaching for my wallet when I remembered: I have tried this. Twice. It does not work here.

If I had written it down the first time, I would have saved myself the money and the disappointment. Failures need recording precisely because we want to forget them.

Timing mistakes worth recording

Timing is where most of my failures live. The gap between “the books say” and “my garden actually experiences” is wider than I expected.

Planted too early

The classic. You get excited by a warm spell in April, plant out your tender seedlings, and a late frost kills them all. I have done this with courgettes, runner beans, tomatoes, and basil. Each time I told myself I would remember. Each time I forgot by the following spring.

What to record: the date you planted out, the date of the frost, what died. “Planted courgettes 25 April, frost 3 May, all dead.” That is all you need. Next year, when April feels warm and you are tempted to plant early, you can check your notes and wait.

Planted too late

The opposite problem, and just as common. You get busy, the weeks slip by, and suddenly it is July and you still have not sown your winter brassicas. They go in late, grow slowly, and never reach a useful size before the cold stops them.

I lost an entire crop of purple sprouting broccoli this way. Sowed in August instead of June, transplanted in September, and by November the plants were still tiny. They survived the winter but never produced more than a handful of florets. A note in my journal now reminds me: “PSB must be sown by end of June or do not bother.”

Sowed indoors too early

You start your tomatoes in February because you cannot wait for spring. By the time it is warm enough to plant them out, they are leggy, root-bound, and stressed. They take weeks to recover, and your carefully nurtured seedlings end up no further ahead than ones sown in April.

Record when you sowed, when you planted out, and how the plants looked. “Tomatoes sown 15 Feb, planted out 20 May, leggy and slow to establish. Next year: sow late March.”

Location mistakes worth recording

Every garden has microclimates. The sunny corner that bakes in summer. The shady bed that stays damp all year. The frost pocket you only discover in May. Learning these takes years of observation, and failures are the fastest teachers.

Wrong sun exposure

I planted a row of peppers along my north-facing fence because that was where I had space. They grew, technically, but they never thrived. Pale leaves, few flowers, tiny fruits that barely ripened. The same varieties in a sunnier spot the following year were transformed.

What to record: where you planted, what you observed, and your theory about why it failed. “Peppers by north fence, poor growth, probably not enough sun. Try south bed next year.” You are building a map of your garden’s light conditions, one failure at a time.

Wrong soil type

Some plants are fussy about soil. Carrots hate stones and heavy clay. Blueberries need acid conditions. Mediterranean herbs rot in wet, rich soil. If you plant something in the wrong spot, it will tell you, usually by dying.

I tried growing lavender in a bed that stays damp through winter. It looked fine for six months, then turned brown and collapsed. The soil was too wet, too rich, too cold. Now I know that bed is for moisture-lovers only. The lavender went into a raised bed with gritty compost, and it has thrived ever since.

Variety mistakes worth recording

Not every variety suits every garden. Climate, soil, disease pressure, and personal taste all play a role. The only way to find out what works for you is to try things and record the results.

Variety not suited to your climate

Seed catalogues are seductive. That Italian tomato sounds wonderful. That French melon looks incredible. But varieties bred for Mediterranean summers often struggle in British conditions.

I have tried and failed with several “exotic” varieties that simply could not cope with my cool, damp climate. Aubergines that never set fruit. Peppers that stayed green until frost killed them.

What to record: the variety name, what went wrong, and whether it is worth trying again. “San Marzano tomatoes, poor ripening, blight by August. Not suited to outdoor growing here. Try under cover or choose a different variety.”

Variety prone to disease

Some varieties are magnets for problems. That heritage tomato might taste incredible, but if it succumbs to blight every year while the modern resistant varieties thrive, you need to know.

I grew Gardener’s Delight tomatoes for years because everyone recommended them. They tasted good, but they caught blight earlier than any other variety in my garden. Eventually I switched to Crimson Crush, which has blight resistance, and my harvests improved dramatically.

Care mistakes worth recording

Sometimes the plant and the location are fine, but you did something wrong. These mistakes are the easiest to fix, if you remember what you did.

Overwatering and underwatering

Container plants are especially vulnerable. Too much water and the roots rot. Too little and the plant wilts and never recovers. The line between the two is narrower than you might think.

I killed a fig tree in a pot by overwatering it through a wet summer. I thought I was being attentive. I was actually drowning it. The leaves yellowed, dropped, and by autumn the tree was dead. Now I check the soil before watering, not the calendar.

Pruning at the wrong time

I pruned my wisteria in spring, not realising it should be done in late summer. No flowers that year. The note in my journal now says: “Wisteria: prune in August, NOT spring.” Timing matters for pruning, and getting it wrong can cost you a year of flowers or fruit.

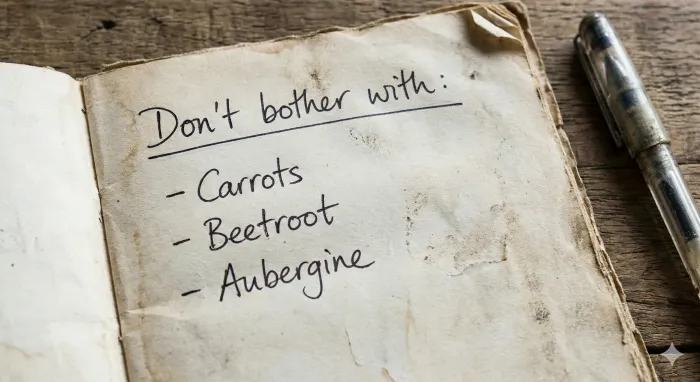

The “never again” list

After a few years of recording failures, a pattern emerges. Some things just do not work in your garden. Not because you did anything wrong, but because the conditions are not right.

This is valuable knowledge. It saves you money and disappointment. Instead of trying the same doomed experiment every few years, you can focus on what actually thrives.

My “never again” list includes:

- Melianthus major (too cold)

- Outdoor aubergines (not enough heat)

- Garlic planted in spring (never bulks up properly)

- Carrots in the clay bed (stones and poor drainage)

- Any tomato variety without blight resistance

Your list will be different. The point is to have one, written down, where you can check it before buying seeds or plants.

How to record failures without feeling bad

The resistance to recording failures is emotional, not practical. It feels like admitting defeat. But reframing helps.

A failure is not a judgment on you as a gardener. It is data about your garden. “Did not work here” is not the same as “I failed.” The plant failed to thrive in those conditions. That is information, not criticism.

Every failure narrows down what does work. If you have tried three tomato varieties and two of them caught blight, you have learned something useful. The third variety is now your reliable choice, tested and proven.

I have improved faster since I started recording everything, good and bad. My journal is full of crossed-out varieties and abandoned techniques, and my garden is better for it.

How Leaftide helps track what went wrong

I built Leaftide partly because I was tired of losing track of my failures. Paper notes got lost or forgotten. Scattered reminders in my phone had no context. I needed a system that would remember for me.

In Leaftide, every planting has a history. When you complete a task, you can add notes about what happened. “Planted out, but too early” or “Frost damage overnight” or “Leaves yellowing, possibly overwatered.” Those notes stay attached to the plant, building a record over time.

When you look at a variety’s history, you see every attempt, including the failures. If you tried San Marzano tomatoes three years ago and they caught blight, that information is there when you are tempted to try them again. You can make an informed decision instead of repeating a forgotten mistake.

The permanent record is what makes the difference. A note attached to a specific plant, searchable and persistent, is there when you need it.

Build your permanent garden memory

Leaftide keeps a history of every planting, including the ones that failed. When you are planning next season, you can see what worked and what did not, all in one place.

What this means in practice

The best garden journals are not the prettiest or the most detailed. They are the ones that help you make better decisions. And the entries you will actually refer back to are often the failures.

Write down what went wrong. Be specific: the date, the variety, the location, your theory about the cause. Do not judge yourself. Just record the data.

The courgettes I plant in mid-May, the tomatoes with blight resistance, the lavender in the raised bed instead of the damp border: all of these came from failures I recorded. The mistakes were the price of the lessons. Writing them down was how I kept the lessons without paying the price again.