I started my food forest six years ago. Fifty trees, two hundred shrubs, countless herbaceous plants. I can name maybe half of them now. The hazel in the corner: is that a Cosford or a Kentish Cob? I genuinely do not know anymore. The label rotted, I did not write it down, and now it is just “the hazel.”

This is the fundamental problem with food forests. They are twenty-year projects, sometimes longer. You are planting for a future you cannot fully imagine, with plants that will outlive your ability to remember what they are. In a vegetable garden, you plant tomatoes in spring and harvest them by autumn. In a food forest, you plant a chestnut sapling and wait a decade for nuts. The timescales stretch beyond human memory, and so do the record-keeping requirements.

A food forest is not just a collection of plants. It is a system of layers, relationships, and succession. What you plant in year one prepares the ground for year five. What you observe in year three informs what you add in year seven. Without records, you are working blind in a project that demands foresight.

Why food forests need better records than regular gardens

Annual vegetables are forgiving of poor record-keeping. If you forget which tomato variety performed well last year, you try a different one this year. The feedback loop is short. You plant, you observe, you harvest, you learn, all within a single season.

Food forests do not work this way. The feedback loop stretches across years, sometimes decades. That nitrogen-fixing shrub you planted to support your apple tree: is it actually helping? You will not know for three or four years. By then, you will have forgotten what you planted and why, unless you wrote it down.

The slow feedback loop. A fruit tree can take five years to produce its first meaningful crop. A hazel needs four or five. During those establishment years, you are investing time and resources into plants whose eventual performance you cannot yet judge. Records let you track that investment and understand what is working.

Seven layers, not one. A vegetable bed has one layer of plants. A food forest has seven. At any given spot, you might have a fruit tree overhead, a nitrogen-fixing shrub nearby, perennial herbs around the base, ground cover spreading underneath, and a vine climbing through. Keeping track of what is planted where requires a system.

Guild relationships matter. In a food forest, plants are not isolated individuals. They are members of guilds, groups planted together because they support each other. A classic apple guild might include comfrey for nutrient accumulation, chives to deter pests, clover for nitrogen fixation. These relationships are the whole point of food forest design. But they are invisible if you do not record them.

Succession planning. What you plant in year one is not what your food forest will look like in year ten. Early plantings are often sacrificial, fast-growing nitrogen fixers that you will remove once the canopy establishes. If you do not record your succession plan, you will forget which plants are meant to stay and which are meant to go.

I learned this the hard way. My early plantings were a scramble of enthusiasm and optimism. I knew what everything was at the time. Now, walking through my food forest, I find plants I cannot identify and guilds whose design logic escapes me completely.

The seven layers and what to track for each

Food forest design is built around seven layers, each with its own role in the system. What you track depends on which layer you are working with.

Canopy layer

The canopy consists of your largest trees, typically large fruit and nut trees like apples, pears, cherries, walnuts, and chestnuts. These are the backbone of your food forest, so their records need to be thorough.

Track: Variety name, rootstock, spacing from neighbours, planting date, source nursery. Rootstock matters enormously for final size. An apple on M27 stays tiny; the same variety on a seedling rootstock becomes a standard tree. If you forget the rootstock, you cannot predict the tree’s mature size.

Also track establishment progress. When did it first flower? When did it first fruit? How did it respond to pruning? These milestones tell you whether the tree is developing normally or struggling.

Understory layer

Smaller trees that grow beneath the canopy: dwarf fruit trees, hazels, elders, mulberries. They occupy the space between the canopy and the shrubs.

Track: Same as canopy trees: variety, rootstock where applicable, spacing, planting date. Additionally, note light conditions. Understory trees must tolerate partial shade. If one is struggling, knowing its light exposure helps diagnose the problem.

Shrub layer

Berry bushes, currants, gooseberries, hazels, nitrogen-fixing shrubs like Elaeagnus. This layer provides much of a food forest’s early productivity while the canopy establishes.

Track: Variety, planting date, source. For fruiting shrubs, track yields. Even rough estimates (“two bowls of currants”) help you compare years and identify your best performers. For nitrogen-fixing shrubs, note their purpose in the system and when you plan to coppice or remove them.

Herbaceous layer

Perennial vegetables, herbs, and support plants. Comfrey, lovage, sorrel, mint, chives, rhubarb. This layer fills the gaps between woody plants.

Track: Variety, planting date, location within guilds. Establishment success is the main metric, as herbaceous perennials can take a year or two to really settle in. Note which ones spread aggressively and which struggle to hold their ground.

Ground cover layer

Living mulches that cover bare soil: strawberries, clover, creeping thyme, Ajuga, violets. They suppress weeds, retain moisture, and add to the system’s productivity.

Track: Species, planting date, initial coverage area. Then track spread. Ground covers are meant to expand. Noting how quickly they fill in tells you which ones suit your conditions. Also note which ones become invasive and need management.

Vine layer

Climbing plants that use vertical space: grapes, kiwis, hops, climbing beans, passionfruit. They need support structures and often training.

Track: Variety, planting date, support structure type, training method. Vines require ongoing management: pruning, tying, training. Record these tasks so you can see how your management affects productivity.

Root layer

Root vegetables and tubers that occupy underground space: Jerusalem artichokes, skirret, oca, Chinese artichokes. They add another dimension of productivity without competing for above-ground space.

Track: Species, planting date, harvest yields. Unlike annual root vegetables, perennial root crops stay in place for years. Note how they persist, whether they spread, and how harvesting affects subsequent years.

Tracking guilds and plant relationships

Individual plant records matter, but food forest design is really about relationships. Plants are grouped into guilds, combinations that support each other. A guild is not just plants that happen to be near each other. It is a designed system where each member plays a role.

A traditional apple guild might include:

- The apple tree: the productive centre

- Comfrey: nutrient accumulator, chop-and-drop mulch source

- Chives and garlic: pest deterrents around the base

- Clover: nitrogen fixation, ground cover

- Nasturtiums: trap crop for aphids

- Daffodils: toxic to voles that might damage roots

Each plant is there for a reason. But reasons fade from memory. Three years from now, you might look at that patch of chives and wonder why you planted them there. The answer is in the guild design, but only if you recorded it.

For each guild, track:

- Which plants are grouped together

- What role each plant plays (nitrogen fixer, nutrient accumulator, pest deterrent, pollinator attractor)

- How the guild performs over time

- What fails and what thrives

Guild performance is the real test of food forest design. Some combinations work beautifully. Others fail. The comfrey might outcompete the chives. The clover might not establish. The nasturtiums might attract aphids rather than trapping them. These failures are valuable information, but only if you record them.

In my food forest, I have guilds I designed carefully and guilds that happened by accident. The deliberate ones have records. The accidental ones are a mystery. When something works in an accidental guild, I cannot replicate it because I do not know what made it work.

The establishment timeline

Food forests develop in phases, and what matters changes as the system matures.

Years one to three: heavy input, many failures

The early years are chaotic. You are planting constantly. Mortality is high. Young trees struggle. Ground covers fail to establish. Nitrogen fixers grow vigorously while the trees they support barely move.

What to track: Every planting, with date and source. Every death, with suspected cause. Every replacement. This is the period when you are learning what works in your specific conditions, and every failure teaches you something.

I lost more plants in my first three years than in the subsequent three. Some to drought, some to rabbits, some to winter cold. I did not track the losses systematically, and now I cannot remember which species were problematic. If I were starting again, I would know what to avoid.

Years three to seven: canopy closing, understory establishing

The trees start to grow meaningfully. The canopy begins to close. Shade increases. Some early plantings need removing. The understory starts to fill in.

What to track: Growth rates. Shade patterns. Which plants are being outcompeted. Which nitrogen fixers you are coppicing or removing. This is the period when succession starts to matter.

Years seven and beyond: mature system, harvest focus

The food forest becomes productive. Fruit and nut harvests increase. The system requires less intervention and more management. Pruning and harvesting become the main activities.

What to track: Yields. Pruning schedules. Pest and disease patterns. After seven years, your food forest has a history worth preserving.

Records from the early years become invaluable in the mature phase. Why is that corner unproductive? Perhaps because of the three trees you lost there in year two. Why does that apple guild thrive? Perhaps because of the design decisions you made in year one.

What to record each season

Food forests are not static. Each season brings changes worth recording.

Spring

- New plantings with variety, source, cost, and exact location

- Blossom timing for fruit trees (useful for pollination planning)

- Frost damage after late cold snaps

- Emergence of herbaceous perennials

Summer

- Growth observations (what is thriving, what is struggling)

- Pest and disease sightings with photos if possible

- Pollinator activity (which plants attract bees)

- Early harvests from soft fruit

Autumn

- Harvest yields by species and variety

- Fruit quality observations

- Chop-and-drop mulching (which plants you cut and where you applied the material)

- Planting of new trees and shrubs (autumn is ideal for bare-root planting)

Winter

- Pruning records (what you removed and why)

- Coppicing of nitrogen fixers

- Deaths and losses discovered as growth stops

- Planning for next year based on the season’s observations

Always

- Wildlife observations: what pollinators you see, what pests appear, what beneficial insects you notice

- Weather events: late frosts, droughts, unusually wet periods

- Tasks you meant to do but did not get to (these become next season’s reminders)

Mapping your food forest

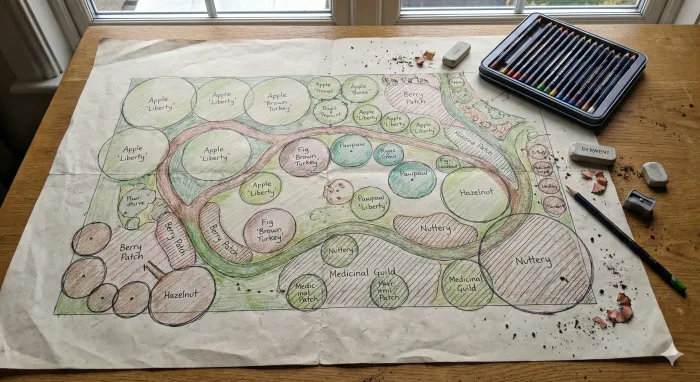

You will forget where things are planted. I guarantee it. A plant that seemed memorable at planting becomes invisible once surrounded by growth. That elderberry you carefully positioned is now somewhere in the back corner, but where exactly?

A map solves this. It does not need to be elaborate. Even a rough sketch with numbered positions helps. The goal is to be able to stand in your food forest with your map and identify what is growing where.

Simple approaches:

- Sketch on paper. Draw your space, mark tree positions, number them to match your plant records.

- Photo with annotations. Take an overhead or wide-angle photo, mark plants using an image editor or even printed and hand-labeled.

- Digital map. If you are comfortable with technology, tools like Google Earth, QGIS, or even a drawing app can create updatable maps.

The map is not a one-time exercise. It needs updating as plants grow, die, and get replaced. A map from year one looks nothing like the same space in year seven. Regular updates keep it useful.

I did not map my food forest in the early years. I thought I would remember. I was wrong. Now I am reconstructing the map from memory and observation, which takes far longer than maintaining one would have.

How Leaftide helps track food forests

I built Leaftide for tracking plants across years, which makes it suited for food forest record-keeping. Each tree, shrub, and perennial becomes a permanent plant with its own profile.

Every plant gets a record with variety name, planting date, source, and location. When you prune a fruit tree, you log it against that specific tree. When you harvest hazelnuts, same thing. When you notice a problem, you add a note with a photo attached. Each entry is timestamped, building a timeline that stretches across years.

The photo attachment feature is particularly useful for food forests. Establishment progress over time. Disease symptoms you want to identify later. Harvest quality. A food forest is a visual system, and photos capture what words miss.

For tracking layers and guilds, you can use descriptive plant names such as “Apple - Canopy - Main Guild” or “Comfrey - Herbaceous - Apple Support” to organise your records by function. This makes it easy to review all your canopy trees together or see all the plants in a specific guild.

The goal is not to create busy work. It is to have the information there when you need it, years after you first recorded it.

Build your permanent garden memory

Every tree, shrub, and perennial in your food forest gets its own profile, with variety, planting date, and full care history. Track establishment progress year by year and learn what works for your system.

Learn more about tracking permanent plants in Leaftide

Starting mid-project

Perhaps you are reading this with an established food forest and no records. Perhaps you planted enthusiastically for years and now cannot remember what half of it is.

This describes me perfectly. My food forest was five years old before I started systematic record-keeping. It is not too late.

Walk through and document what you know. For each plant you can identify, create a record. Variety if known, approximate planting date, location. Even “unknown hazel, north corner, planted around 2021” is better than nothing.

Identify unknowns over time. Take photos of leaves, bark, fruit, flowers. Use identification apps. Ask in forums. As you identify plants, add the information to your records.

Draw a map now. Even a rough sketch. Number each plant position. This becomes your reference as you build up records.

Start recording from today. You cannot reconstruct the past perfectly, but you can capture everything going forward. Next pruning, note it. Next harvest, note it. Next observation, photograph it.

Within a year, you will have a year of data. Within three years, patterns will emerge. The best time to start was when you planted your first tree. The second best time is now.

The long view

A food forest is an inheritance. If you do it well, it will outlast you. The trees you plant today could be productive for your grandchildren. The system you create could feed people for generations.

This timescale requires a different relationship with record-keeping. You are not just noting what you did for your own reference. You are creating a history of the place.

What varieties did you plant and why? Which guilds worked and which failed? What was the progression from open field to closed canopy? How did the system develop, year by year, from bare land to productive forest?

These records have value beyond your own memory. They are the institutional knowledge of your food forest. Without them, every new generation starts from scratch. With them, the learning compounds.

I cannot remember which hazel is in my corner. I wish I had written it down. But I can make sure that everything planted from now on is documented. And I can make sure that whoever tends this land after me knows what they are working with.

That is the gift of good records: not just a better garden, but a garden that remembers itself.

Sources and further reading

For food forest design principles and practical implementation:

- Permaculture Association: Food Forests: UK-focused food forest guidance

- Plants for a Future: Comprehensive database of useful plants for permaculture systems

- Agroforestry Research Trust: Research and resources on forest gardening

- Permies.com: Active permaculture community with extensive food forest discussions

For related tracking approaches:

- Home Orchard Record Keeping: Simpler system for fruit trees

- Permanent Plant Tracking in Leaftide: How to set up ongoing plant records